With a central cavern measuring 350 by 215 by 430 ft, the 10 million year old Grotta Gigante in northeastern Italy is the second largest cave in the world open to tourists. The 10 million year old cave was first explored in 1840 by a spelunker hoping to find a water source at its bottom, but, alas, the river that carved the cave had left it 3 million years prior! The elusive "disappearing" Timavo River enters the ground near the mountains and exits near the sea, its underground course through the carbonates of the Karst Plateau still largely a mystery. Read more

Grotta Gigante in Trieste, Italy

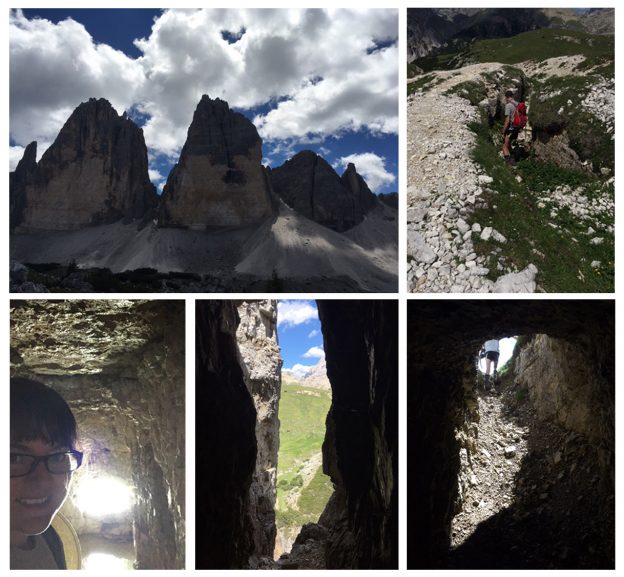

Military Geology of Tre Cime Nature Park

I recently completed an internship in Trieste, Italy, the highlight of which was a day hike around the Tre Cime Nature Park in the Dolomites. On top of the incredible geology, the park features relics of the World War 1 front between Austria and Italy, such as the pictured trench and cave dug into the carbonate rocks. Besides tunnels, other war uses of the geology included the use of explosions to trigger fatal rock slides. I can't imagine fighting and hauling heavy equipment across (and up!) this rugged terrain. Read more →

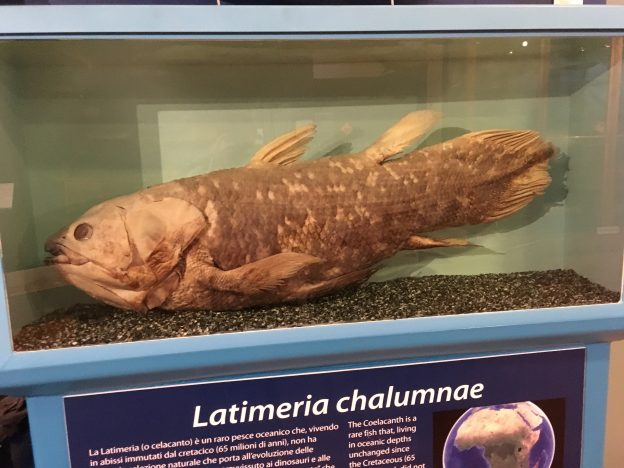

Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) in Trieste's Natural History Museum

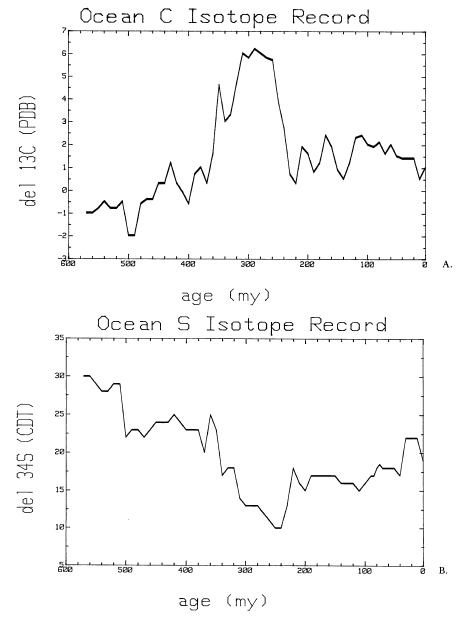

Seawater isotope ratios through time: sulfur and carbon

Low sea levels = heavy carbon, light sulfur in seawater

- Low sea levels = more land space for plants = plants use lighter carbon = lighter carbon stuck on land = heavy carbon in the sea!

- Low sea levels = less habitat for sulfate-reducing bacteria = less light sulfur in pyrite = more light sulfur in the sea!

High sea levels = light carbon, heavy sulfur in seawater

- High sea levels = less space for plants = less light carbon uptake by plants = light carbon in the sea!

- High sea levels = expanded habitat for sulfate-reducing bacteria = more light sulfur in pyrite = less light sulfur in the sea!

Subducted seawater the source of fluid-rich diamonds

Subducting oceanic plates that dive hundreds of kilometers beneath Earth’s surface carry with them cargoes of sediment and seawater. As the plate heats up the deeper it sinks, this seawater not only initiates melting in the rock above it, but can also trigger diamond formation, suggest the authors of a new study in Nature. Read more →

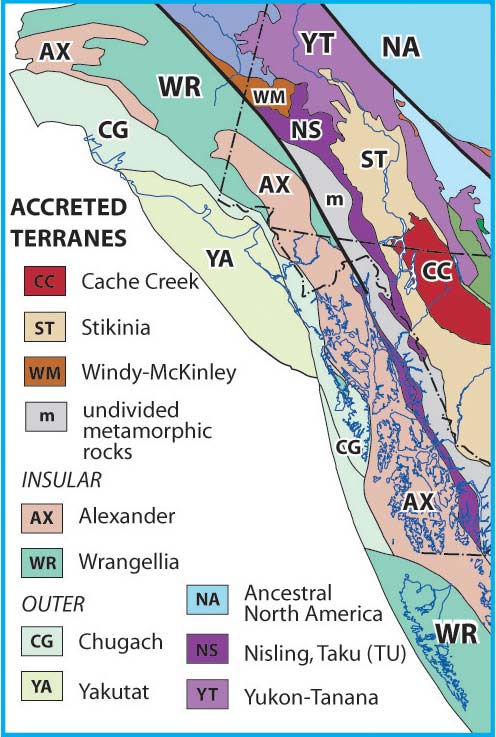

How the west was made: western North American orogenies

Western North America is a patchwork is hundreds of terranes, which are crustal pieces or microplates (think of islands), that collided with and attached to North America across hundreds of millions of years -- adding piece-by-piece to the continent's width and building mountains as they produced volcanoes or pushed up sediments and rocks. This posts provides a very simplified timeline of the major orogenies and terranes that affected western North America. For a more in-depth look, see the resources below. Read more →

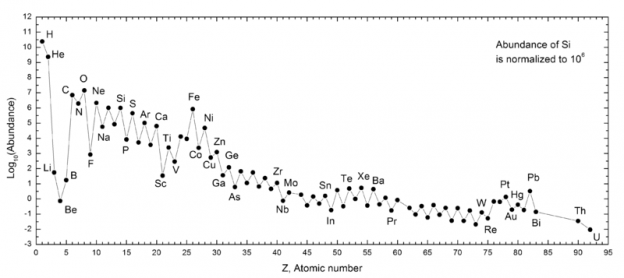

Nucleosynthesis: the births of the elements

How were the elements made? What explains the relative abundance of each element in our solar system? Below you will find a very simplified overview of nucleosynthesis, the process by which elements are formed in the burning hearts of stars. For additional information, start here. Read more →

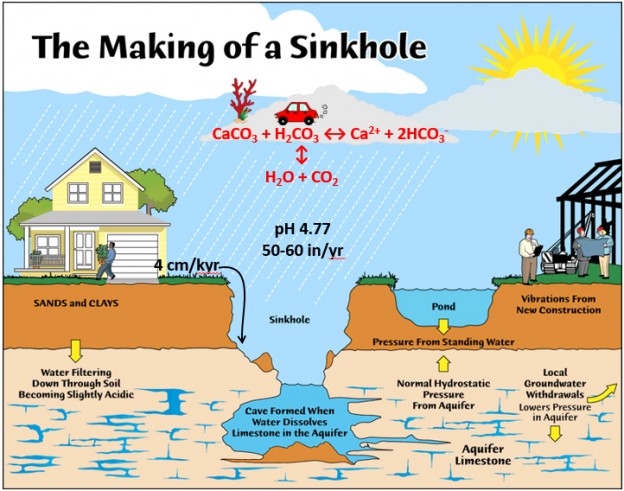

Chemistry lesson: calcium carbonate solubility

The big equations:

CaCO3 ⇌ Ca2+ + CO32-

CaCO3 (s) + H2CO3 (aq) ⇌ Ca2+ (aq) + 2HCO3- (aq) Read more →

Easy Science: How sinkholes form

Sinkholes can form anywhere that the bedrock dissolves away beneath the soil, but classic sinkholes tend to form in limestone, a carbonate rock composed primarily of the minerals calcite (CaCO3), aragonite (CaCO3), and dolomite (CaMg[CO3]2). Worldwide, limestones cover about 15% of land surface. Twenty percent of the US is susceptible to sinkholes. Read more →

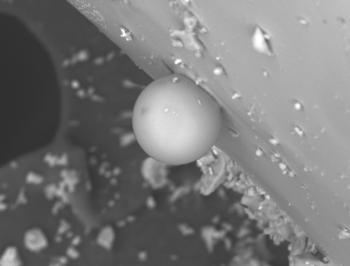

Volcanic lightning turns ash into glass

Within the ash plumes of explosive volcanic eruptions, collisions among countless pyroclastic particles sometimes lead to the buildup of static charges that discharge dramatically as volcanic lightning. In a new study, researchers have found that this lightning can, in turn, melt and fuse ash particles into distinctive glassy grains called spherules. Identifying and studying these spherules could help scientists better understand past and future eruptions, the study’s authors suggest. Read more →