Note: This was written for a school project. It will be featured as a chapter in an Apple iBooks textbook released by Duke University about Beaufort marine invertebrates.

Latin Name: Squilla empusa (Mantis Shrimp)

Taxonomy: Animalia (Kingdom) > Arthropoda (Phylum) > Crustacea (Subphylum) > Malacostraca (Class) > Hoplocarida (Subclass) > Stomatopoda (Order) > Unipeltata (Suborder) > Squilloidea (Superfamily) > Squillidae (Family) > Squilla (Genus)

Habitat & Abundance: Sandy or muddy bottoms along the Western Atlantic coast; average of one mantis shrimp per m2 in summer.

Habitat & Abundance: Sandy or muddy bottoms along the Western Atlantic coast; average of one mantis shrimp per m2 in summer.

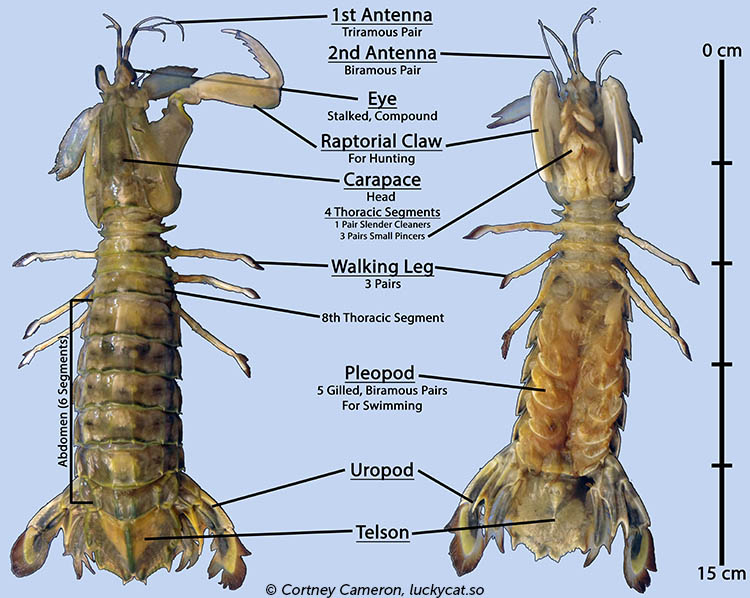

Size: Up to 20 cm long.

Anatomy:

- Dull greenish to yellowish color.

- Bright green eyes on stalks.

- Long, flattened, segmented body with carapace, thorax, and abdomen.

- Pair of long, serrated raptorial claws, typically folded under carapace.

- Three pairs of walking legs on thorax.

- Swimming pleopods (five pairs) on underside of abdomen.

- Spiny telson flanked by uropods.

Conservation: Not threatened; eaten as a delicacy in some areas.

Description & Fun Facts:

Squilla empusa excavate and inhabit U-shaped burrows, which have two openings, in muddy or sandy bottoms down to 55 meters in saline waters. The larger the mantis shrimp, the larger its burrow: up to 15 centimeters deep and 2 meters long, with openings of 10 centimeters in diameter. Mantis shrimps defend their burrows against other mantis shrimps, although during mating season, males leverage their burrows to attract females.

As carnivores, S. empusa hunts fish. It waits at the opening of its burrow for its prey to swim overhead, then uses its raptorial claw to snatch the fish. Mantis shrimp are prodigious hunters that can move their specialized appendages at neck-break speeds. The raptorial claw hits prey within 4-8 ms of initiation at a velocity of 10 meters per second. As needed, S. empusa will use their claws against other S. empusa; while this can lethally injure the opponent, severe injuries rarely occur.

Mantis shrimp, which are often accidentally caught in trawling nets, have earned the nickname “thumb-splitters” from fishermen. In recent years, the notable abundance of S. empusa has attracted the interest of commercial fisheries, but while mantis shrimp is considered a delicacy in several countries, the trend has yet to pick up in the United States.

S. empusa lives up to 3 years and can weigh up to 90 grams, with females typically growing larger than males.

The acrobatic mantis shrimp can fold itself over segment-by-segment to turn around, which no doubt comes in handy for navigating its narrow burrow. A quick-escape reaction causes the mantis to instantaneously dart backwards several inches, so that it still faces its threat. One scientist described these unique locomotive techniques as “somersaulting”.

The mantis shrimp, named for its mantis-like raptorial claws and its shrimplike body, clearly isn’t a praying mantis, but neither is it a shrimp. Although shrimp and S. empusa both belong to the Class Malacostraca, mantis shrimp are stomatopods and shrimp are decapods. As an example of an important difference between the groups, shrimp have five pairs of thoracic appendages (hence the name decapod, which means “ten feet”), while mantis shrimp only have three.

Most mantis shrimp live in clear tropical waters, but S. empusa lives in murky waters, a habitat that has caused it to develop some differences from to its sunnier relatives. Tropical mantis shrimp, which often have dazzlingly colorful bodies, use an amazing (humans have three) to hone in on their prey, which they smash rather than spear; however, since less light reaches S. empusa’s environment, not only have their bodies become drab, they have lost all but one receptor type. Tropical mantis shrimp live in pre-existing rock or coral tunnels; for this reason, burrows are limited, making tropical mantis shrimp much more aggressive. S. empusa, which can construct its own home and thus need not compete for one, is markedly reclusive by comparison, making it more difficult to study.

References:

- Burrows, The mechanics and neural control of the prey capture strike in the mantid shrimps Squilla and Hemisquilla, Zeitschrift für vergleichende Physiologie14. May 1969, Volume 62, Issue 4, pp 361-381, http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00299261#page-1

- Chesapeake Bay Program. http://www.chesapeakebay.net/fieldguide/critter/mantis_shrimp

- Myers. Summer and winter burrows of a mantis shrimp, Squilla empusa, in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island (U.S.A.). Estuarine and Coastal Marine Science. Volume 8, Issue 1, January 1979, Pages 87–90. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0302352479901075

- Risyuhada, Imam. Density, distribution and life history characteristics of the mantis shrimp, Squilla empusa, in the muddy sediments of Narragansett Bay. University of Rhode Island, ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing, 2011. http://search.proquest.com/docview/886759106

- Ruppert & Fox. Seashore Animals of the Southeast. University of South Carolina Press, 1998. Page 323.

- Tavares. Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/009/y4160e/y4160e16.pdf

- Trevino & Larimer, The spectral sensitivity and flicker response of the eye of the stomatopod, Squilla empusa. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Volume 31, Issue 6, 15 December 1969, Pages 987–991 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0010406X69918076

- World Register of Marine Species, http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=158466

- Wortham-Neal, Jennifer Lynn. The social interactions and reproductive morphology of a spearer mantis shrimp, Squilla empusa. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing, 2001. http://search.proquest.com/docview/304770523