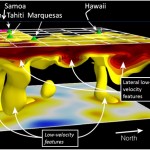

In Hawaii, volcanoes form over a hot spot, an area where magma rises from the mantle and breaks through the crust. The Pacific plate moves northwest over the hot spot—which remains stationary—eventually carrying the old volcano away from the hotspot. A new volcano then begins to form, with repeated basaltic eruptions building a broad shield volcano.

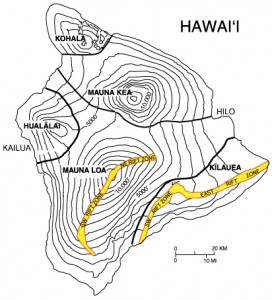

Rift zones of Mauna Loa and Kilauea. Image: University of Hawaii at Hilo

As material continues to accumulate, it eventually becomes too much to support against gravity; the flanks of the volcano then essentially begin to slide away, creating a series of linear fissures called a rift zone.

In Hawaii, since younger volcanoes are usually buttressed by older volcanoes sitting behind them, volcanoes typically develop two rift zones trending in directions opposite or perpendicular to each other; without the support of their elders, the volcanoes might develop four rift zones. True to form, Kilaeua (the youngest above-water Hawaiian volcano) has two well-defined rift zones: the East Rift Zone, and the Southwest Rift Zone. Mauna Loa, the second youngest Hawaiian volcano, also has two—but Hualai, the third youngest, has three, perhaps owing to its position on the island.

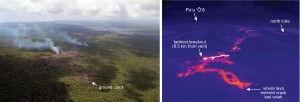

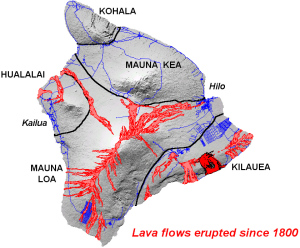

Eruptions tend be highly concentrated around rift zones. Image: University of Hawaii at Hilo

The cracking and splitting of the rocks along rift zones makes them areas of weakness, and since their vents sit at lower elevation than the caldera, lava prefers to erupt from rift zones rather than climbing uphill to the caldera. As a result, eruptions tend be highly concentrated around rift zones.

The Puʻu ʻŌʻō cinder/spatter cone sits along Kilauea's East Rift Zone and has continuously erupted since 1983, adding almost 250 acres of land to Hawaii's southeast coast with beautiful displays of lava pouring into the ocean—but also claiming hundreds of buildings and miles of highway along the way.

Most recently, in late June 2014, new vents opened along the Kilauea's East Rift, and by August, the lava took advantage of ground cracks to travel nearly ten miles away from vents, resurfacing and threatening housing developments and wildlife reserves. By entering ground cracks, lava can avoid the cooling effects of air and flow farther than it would otherwise. The USGS is publishing updates on the flow's status and photographic documentation of its progress.

Given how little is understood of volcanoes' internal plumbing and the behavior of the magma inside, eruptions are notoriously difficult to predict. Early this year, University of Miami researchers released their findings that Kilauea has much deeper, more extensive magma chambers than previously believed. In order to make decisions on evacuations, the USGS closely monitors seismic activity in Hawaii, as increased seismic activity oftentimes preludes volcanic activity.